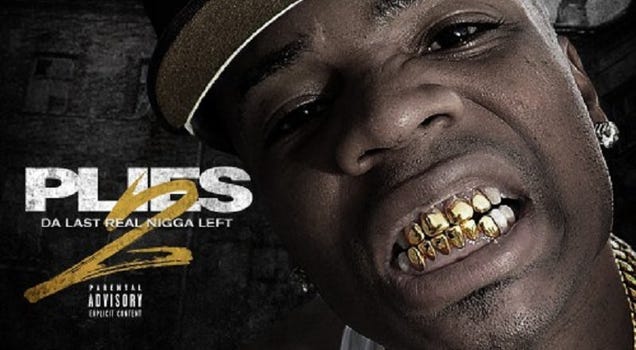

Plies's decade in the rap game—in which he navigated through his native Florida's underground, ascended briefly to mainstream fame via two Gold-selling albums, and has since returned to the Southern rap mixtape circuit—immediately calls to mind one word: "realness." There are the titles of his first three albums: The Real Testament, Definition of Real, and Da REAList. Then there are the mixtapes, like 100% Real, Da Last Real Nigga Left, and the recent followup, Da Last Real Nigga Left 2.

This brand of realness might not be as autobiographical as it appears—despite the copious bars Plies has devoted to prison life, the rapper, a former D1 wide receiver, had no criminal record prior to achieving musical fame—but we're all adults here, and can look past artistic fictionalizations/exaggerations and judge his output on its own merits.

But what is realness to Plies? Many soldiers in the rap-moralizer crusade who believe this form of artistic expression is somehow uniquely unable to see past superficial appearances would tell you that he over-relies on a drug-dealing, gun-toting, criminal-goon persona. Indeed, "goon" is probably right behind "real" when you think about Plies—though it also might be third to his hilarious and continued use of "cracker" as an on-record insult. When you really listen to what Plies is saying, though, it becomes evident where his true interests and inspirations lie: in his relationships with other people.

This is a sentiment that not only goes under-appreciated in rap-traditionalist circles, it has been all but denied to Plies specifically. Many in the rap-blog and message-board world would scoff at even the possibility that he could have the capacity for wisdom and compassion. This blind spot is largely a fluke of timing, aided no doubt by a probably fake but still enduring interview he allegedly gave to Vibe.

When Plies was first popping on the mainstream level back in the late '00s, there was a growing backlash among underground, East Coast-centric rap fans to the Southern rap that had taken over the mainstream. To those fans, any rapper hailing from a city south of D.C. was considered dumb, a sell-out, and not part of what they considered "real hip-hop." The focus on partying, having fun, and/or wanton violence was seen as a fundamental shift from the heady days of the Native Tongues era, when intellectualism and seriousness were the signals of Important Rap.

Plies gave this movement, and its backlash, a face. A number of factors played into this: what his detractors saw as his conflation of "realness" with criminality, revelations that he wasn't actually as "real" as he made himself out to be, and then, the Vibe thing. Plies was on the cover of the December 2008 issue, which itself caused some consternation with the "real hip-hop" police: Why was a no-talent phony headlining one of the more reputable urban-music mags?

Then came an alleged excerpt from the interview within those pages. According to this XXLmag.com blog, Plies gave this hilariously dumb response to a question about where his name came from:

Vibe: Plies is an interesting name for a rapper, how did you get that nickname?

Plies: "Plies" is a tool. You can use it to put the squeeze on things, like I'm doing to these niggas in the rap game. I got the squeeze on them real tight. They feeling the pressure. Or you can use it to pull things out. I pull out all the bullshit and keep the real, you feel me? It also a word you can use in terms of things goin' on in yo life, ya dig. You may hear something I say and say that it "plies to me."

Vibe: I've heard of a tool called a "pliers" and the term "applies."

Plies: You know what I'm trying to say my nigga, just buy my album, I'm from the South, my nigga. We don't learn no grammar. My Album out August 7, 2007. Cop three copies each. It's Christmas in July fo' real, ya dig?

His response was so hilarious, so preposterous, and so perfectly emblematic of the perceived intellectual shortcomings of all the bad Southern rap that had taken over; it has since become the quintessential Plies quote. Indeed, it was the first thing I thought of when we did our own post about a song of his. Among a certain set of rap fans, that interview was the only thing we knew about the rapper.

The thing is, it almost certainly wasn't real. That edition of Vibe is available on Google Books, and none of those quotes appear in the pages. The guy who wrote that XXL article, Ron Mexico City, was a humor columnist for the site (a Vibe rival, by the way), so it's not even clear if he intended the excerpt to be taken seriously. And in another interview on Youtube, Plies himself explains the origins of his name ...

His version, that "Plies" was a general name given to any street cat making moves in his local Ft. Myers neighborhood, makes much more sense. But more important than his setting the record straight is how he goes about doing it. He comes across as perfectly articulate and thoughtful, not at all like the rambling dunce we all wanted him to be. That caricature never really existed, but it has served to limit serious inquiry into what the real Plies is about for far too long.

Da Last Real Nigga Left 2 is a perfect vehicle to investigate Plies's music on his own terms. As we'd expect, the rapper offers us tales in and around the streets with his typical imploringly expressive cadence, backed by the same kind of kinetic, dark beats that make up the modern Atlanta sound. While most every song could get run in a club purely on the energy it evokes in any listener with a pulse, there's just as much going on lyrically as sonically.

As any beloved gangster film proves, the heart of those crime stories doesn't solely lie in the meticulously planned, perfectly orchestrated climactic bank heists or the disquieting visuals of everyday items riddled by unending streams of bullets; no, the core of those movies is the relationships between the characters. The dead bodies serve to make it easier for us to attribute morality to the shooters; the life-or-death stakes give us a compelling reason to invest in the outcomes. Without Tony and Manolo's friendship, the conflicted Montana family dynamics, and the drive of the characters to finally attain self-sufficiency after so many generations of submission, Scarface would merely be an empty couple hours spent raising hell in Grand Theft Auto: fun, but ultimately unsatisfying. (Hopefully.)

Plies's music has always been primarily concerned with these smaller moments between the big set-pieces of his goon stories, and Da Last Real Nigga Left 2 is no different. Of the mixtape's 21 tracks, only a handful are of the straightforward snappin'-and-trappin' goonery type. And even on many of those songs, he mediates his material success and street travails through the effects on those around him.

On "Know What I'm Sayin," Plies toasts to the good life he has provided for both himself and his friends; while he doesn't regret his decision to pursue a criminal lifestyle on "Ain Look Back Since," he does spend time remembering the family members that put him on in the game. Even on the beef track "War & Peace," he comes off like he's earnestly advising someone, rather than merely spouting threats at disembodied enemies. At almost every turn here, he seems to be in real-life conversation with real-life people.

Like most rappers, his friends play a large role in these affairs. "Did It Outta Luv" paints the successful rapper as not quite a Godfather figure, but definitely something of a big brother to his cohorts: The chorus starts, "You will never owe me shit, nigga / I did it outta love." Also, "Would they have done it for me? My nigga, it don't fucking matter / I was able to do it for them, to me that's all that fucking matters."

This isn't just about money. Plies is also a reliable fount of advice, especially where relationships are concerned. "Dat Ain't Yo Bitch" and "Got U Gone Man" both chastise a man for allowing an unworthy woman to get them open. Naturally, the former track is the less sympathetic of the two. Here's how it starts: "This is a public service announcement, man. PSA. To all the lame-ass niggas that got the game fucked up: That ain't your bitch, man!" The point here is that men who meet women who very obviously aren't looking for anything serious—definitely nothing serious from these simps—are hustling backwards if they think that lavish gifts and expensive dates will buy loyalty.

While this may appear to be your standard "Captain Save A Hoe" fare, Plies actually has a refreshing clarity on who's really to blame for these situations: the clueless guys. He sees the women's behavior as the completely rational response that it is: "Think caking on the bitch, dog, you gon' tame her? / I hope she breaks your punk ass, I don't even blame her." Not only that, he sees the negative repercussions this delusional belief of ownership can engender, and denounces it:

You ain't a motherfuckin' player, you a sponsor, nigga

Y'all niggas rent the game on mommas, nigga

Then get mad, find out the ho don't like you for real

Go to threatening the hos, ain't that some shit

Y'all niggas go to acting like the hos to me

Fuck niggas get played like they s'posed to be

"Got U Gone Man"—meaning, as the chorus tells us, "That pussy got you gone, man / That lil' ho running circles round you, bruh"—sees this lame-assness infiltrating someone in his circle. But here, Plies shows more concern than scorn: "If you in love, then you in love, but being stupid's something else." And again, he doesn't blame the woman. At one point, the scenario verges on dangerous, with implications of domestic violence. Here, Plies is quick to implore his friend to extricate himself from the situation: "If you got to whoop the ho to keep the ho, then you don't need to be there / Ain't no ho gon' put me in jail and we gon' get back together."

He's not just a love guru, either. "U Betta Watch" sees him warning people that "Everybody ain't real"; after all, Da REAList can't go around blabbing all of his oft-criminal business to just anybody. Plies draws from not only his own firsthand experiences, but also on those of his family members who've been done in because of untrustworthy associates: "Thinking everybody straight's what got my uncle and 'em harmed / My cousin thought the same shit, now he's sitting with no bond." Family teaching family teaching friends. Community.

Of course, this wouldn't be a Plies production if we didn't get a look into our narrator's own trials and tribulations with women. It seems he takes his own advice about avoiding bad relationships, since most of the songs here from his point of view are positive, or at least started out that way. The title of "Ride or Die" gives you a good hint as to what the song's about: Yes, he raps about how down his girl is for his cause, willing to hold him down in times of trouble both personally and "professionally" (i.e., she won't rat him out to the cops). But more than that, it's about not being so possessive of a woman who clearly loves you: "She can club a little bit, but she don't need that shit / She can shut it down tomorrow, don't even miss that shit."

The sentiment might be a little more poignant if you are, as Plies tends to imply, under constant threat of being locked up. "I hope it don't happen, but if I did go to jail / I know she gon' hold me down, pick up the phone and send me mail." He's not stressed about other guys around town hollering at his girl in his time of incarceration, either, because of the trust he has for her: "You know how niggas sometimes close to you get creep / Try to back door ya, shoot at her, see if she'll cheat / All I can tell you, dog, if you get it you good / And I ain't gotta tell you you creep, she'll say it to you first."

"Smile" and "Jump" likewise showcase a happily-in-love Plies. When he's serious about somebody, he's willing to spend money on her to make her happy, even if he has a clunky way of putting it: "See some of them Chinese people so they can paint your nails / Give your cousin a couple hundred dollars for doing your hair / When you're happy, babe, I'm happy / When you're sad, it hurts." He also reveals what he considers to be the ultimate sign of commitment: "Shit, your momma know my momma, which means it's legit." But don't expect it to get much more serious than that: "You got a real nigga thinking 'bout jumping the broom / I was just playing, cuz that might be too soon."

You had to figure you'd get some funny lines out of Plies on the topic of " dat pwussy," and "Jump," the designated Fucking Song, is where you'll find them. We won't give them all away, but a couple good ones: "Call me when you're coming out the shower / I'll be in your bed waiting on you in a towel / Let that pussy air-dry like a flower"; "Let me feed the banana to that monkey / Throw that pussy back at me like you're mad, bae"; "I don't even want it, baby, if you ain't a nympho / If he don't eat it from the back, it's an insult." And so on.

Alas, despite Plies's best intentions, not all his relationships are as cheery. "Issues" is one example: "One minute you're a killer, next minute you're crying / One minute you don't fuck with me, next minute you're riding," he laments. Times like that remind him of the wisdom of his family, though: "Like my auntie used to say, 'Bitch, your bread ain't done.'"

Other times, he admits that he's the transgressor, as on "2 Good 4 Me." It's a perfectly common story of two people with different objectives in a relationship, made unique by the same introspection and self-awareness that typifies the rest of the tape:

You was looking for love, I was looking for licks

You really cared about a nigga, I was so full of shit

I was moving too fast, the streets was soaking me up

I neglected you and all, and damn, that was fucked up

But I was thinking about you, I guess that wasn't enough

You was holding me down, but I wasn't holding you up

Eventually, the late nights spent getting money made his girlfriend suspicious, and the relationship deteriorated. Plies insists that it really was the money that he was chasing, not other women, and his explanation about the importance of money in the culture of street cats he runs with is revelatory:

The same time you was calling, baby, so was the bread

And I don't know if you'll understand: Without the paper, you're dead

I was just grinding, I promise, I was gon' get right back

But if you did it to me, I wasn't going for that

They say we do unto others you want to do unto you

But one thing about a street nigga, we don't play by the rules

I just thought 'cause you love me that you'll forever understand

But like my momma always told me, that's just an excuse for a man

"Mad at Myself," naturally, is another example of the rapper refusing to blame others for his troubles, even if he has good reason to do otherwise. The chorus goes, "When I was broke, wasn't mad at nobody but myself / I showed you love, I got you pussy, I'm mad at myself / Thought you were gonna ride and you ain't ride, I'm mad at myself / I found out you wasn't shit, I'm mad at myself."

The first verse is apparently aimed at a former love of his who "switched out on" him, though he forgave her; the second is more of a general explication of what is basically his "forgive but don't forget" mantra: "If a nigga gon' ride, then he gon' ride / You don't have to tell 'em / If a bitch gon' ride, then she gon' ride / You don't have to beg 'em." Even in the face of actual betrayal, Plies looks inward on what he could've done differently rather than point the finger.

The darkest of the introspective songs here is definitely "Daddy," which imagines what Plies's life would've been like if his father would've stuck around and raised him instead of leaving the family when he was young; the rapper concludes that he "probably wouldn't have been shit" if that were the case, as the lack of a father figure only made him hungrier:

Soon as my daddy left

Had to grow up fast

Couldn't run to him for help

Had to get up off my ass

Had to get down in these trenches

Had come up with a plan

Had to start making power moves

Nigga had to get some cash

Where so many fatherless rappers express nothing but resent for their absentee dads, Plies claims he has no such animosity: "Dad, I still fuck with him / I ain't mad at him at all / Did what he had to do / I did what I had to, dog."

It's a strange sentiment, but it's in character. Plies doesn't make excuses for what has befallen him, be they problems of his own making or not. Whenever something doesn't go right, he's ready to assess how he personally can avoid the situation in the future and is willing to share his experiences with others in hopes that they avoid the same traps that ensnared him.

What Plies may have missed in a father, he has attempted to make up for in the form of other family, friends, and lovers. The culmination of this self-forged identity, as expressed through his music, may not have created the most technically gifted rapper in the game, nor one with interests that venture too far from the streets, nor even the most strictly honest figure in hip-hop. But taken all together, fact and fiction, Plies is unquestionably real.

The Concourse is Deadspin's home for culture/food/whatever coverage. Follow us on Twitter.

0 comments:

Post a Comment